For almost 100 years, the Panama Canal represents an indispensible shortcut for the global shipping industry and is a key economic factor for the people of Panama.

Its prominent expansion in progress aims to further maximize Panama’s strategic geographic location by helping it become an international maritime hub at the center of global trade. Being also indispensible for BBC Chartering, we take this opportunity to highlight efforts underway to improve the world’s ‘All-Water Route’.

Profiling the Canal

The Panama Canal is approximately 80 kilometers long and connects the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. This waterway was cut through one of the narrowest saddles of the isthmus that joins North and South America. The Canal uses a system of locks with entrance and exit gates.

The locks function as water lifts: they raise ships from sea level (the Pacific or the Atlantic) to the level of Gatun Lake (26 meters above sea level); ships then sail the channel through the so called ‘Continental Divide’.

Each set of locks bears the name of the town-site where it was built: Gatun (on the Atlantic side), and Pedro Miguel and Miraflores (on the Pacific side). The existing lock chambers measure 33.53 meters by 304.8 meters. The maximum dimensions of ships that can pass the Canal are: 32.3 meters width; 12 meters draft; and 294.1 meters length.

The water used to raise and lower vessels in each set of locks comes from Gatun Lake by gravity; it flows into the locks through a system of main culverts that extend under the lock chambers from the sidewalls and the center wall.

The narrowest portion of the Canal is Culebra Cut, which extends from the north end of Pedro Miguel Locks to the south edge of Gatun Lake at Gamboa. This segment, approximately 13.7 kilometers long, is carved through the rock and shale of the Continental Divide.

Ships from all parts of the world transit daily through the Panama Canal. Some 14,000 thousand vessels use the Canal p.a. breaking a record every year. In fact, commercial transportation activities through the Canal represent approximately 5% of the world trade. The Canal has a work force of approximately 9,000 employees and operates 24 hours a day, 365 days a year, providing transit service to vessels of all nations without discrimination.

A gigantic project – upgrading the canal

As demand is rising for efficient global shipping of goods, the canal is positioned to be a significant feature of world shipping for the foreseeable future. However, changes in shipping patterns—particularly the increasing numbers of larger-than-Panamax ships—will necessitate changes to the canal if it is to retain a significant market share. Current estimates suggest that 37% of the world‘s container ships are too large for the present canal, and hence a failure to expand would result in a significant loss of market share. The maximum sustainable capacity of the present canal, given some relatively minor improvement work, is estimated at between 330 and 340 million PC/UMS tons per year by 2012. Close to 50% of transiting vessels are already using the full width of the locks.

An enlargement scheme similar to the 1939 Third Lock Scheme, to allow for a greater number of transits and the ability to handle larger ships, has been under consideration for some time. It has been approved by the government of Panama in 2006 and currently is in progress with completion expected in 2014. The cost is estimated at US$ 5.25 billion for the doubling of the canal‘s capacity that facilitates more traffic and the passage of longer and wider ships. This proposal to expand the canal was approved in a national referendum where it received a majority of approximately 80% of the Panama people.

Third set of locks project

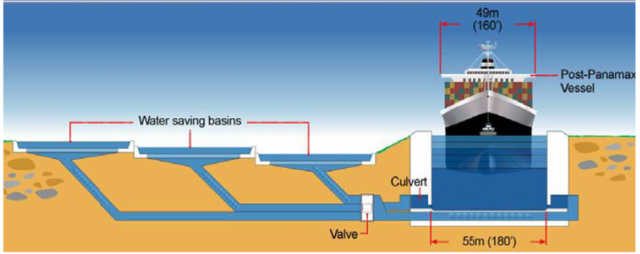

It has been decided to build two new flights of locks parallel to the old locks: one to the east of the existing Gatún locks, and one south west of Miraflores locks, each supported by its own approach channel. Each flight will ascend from ocean level direct to the Gatún Lake level in three stages; the existing two-stage ascent at Miraflores/ Pedro Miguel will not be replicated, but the old locks will continue service. The new lock chambers will feature sliding gates, doubled for safety, and will be 427 meters (1,400 ft) long, 55 meters (180 ft) wide, and 18.3 meters (60 ft) deep. This will allow the transit of vessels with beams up to 49 meters (160 ft), an overall length of up to 366 meters (1,200 ft) and a draft of up to 15 meters (50 ft). This is equivalent to a container ship carrying around 12,000 containers, each twenty feet (6.1 m) in length (TEU)

Prominent waterway charges

It is said, that the most expensive regular toll for canal passage to date was to the cruise ship Coral Princess, which paid US$380,500. The least expensive toll was 36 cents to American adventurer Richard Halliburton, who swam the canal in 1928. The average toll is around US$54,000. The highest fee for priority passage charged through the Transit Slot Auction System was US$220,300, paid on August 24, 2006 by the Panamax tanker Erikoussa, bypassing a 90-ship queue waiting for the end of maintenance works on the Gatun locks, thus avoiding a seven-day delay. The normal fee would have been just US$13,430.

The toll system in general

Tolls for the canal are decided by the Panama Canal Authority and are based on vessel type, size, and the type of cargo carried.

For container ships, the toll is assessed on the ship‘s capacity expressed in TEU (twenty-foot equivalent units).

The toll is calculated differently for passenger ships and for container ships carrying no cargo (‘in ballast’).

Most other general cargo vessels pay a toll per PC/UMS net ton, in which one „ton‘ is actually a volume of 100 cubic feet (2.83 m3). Also here, a reduced toll is applicable for freight ships in ballast.

Passenger vessels in excess of 30,000 tons (PC/UMS), known popularly as cruise ships, pay a rate based on the number of berths, that is, the number of passengers that can be accommodated in permanent beds. Here the per-berth charge is currently $92 for unoccupied berths and $115 for occupied berths.

The locks will be supported by new approach channels, including a 6.2 km (3.9 mi) channel at Miraflores from the locks to the Gaillard Cut, skirting Miraflores Lake. Each of these channels will be 218 meters (715 ft) wide, which will require post-Panamax vessels to navigate the channels in one direction at a time. The Gaillard Cut and the channel through Gatún Lake will be widened to no less than 280 meters (918 ft) on the straight portions and no less than 366 meters (1,200 ft) on the bends. The maximum level of Gatún Lake will be raised from 26.7 meters (87.5 ft) to 27.1 meters (89 ft).

Each flight of locks will be accompanied by nine water reutilization basins (three per lock chamber), each basin being approximately 70 meters (230 ft) wide, 430 meters (1410 ft) long and 5.50 meters (18 ft) deep. These gravity-fed basins will allow 60% of the water used in each transit to be reused; the new locks will consequently use 7% less water per transit than each of the existing lock lanes presently in use. The deepening of Gatún Lake, and the raising of its maximum water level, will also provide significant extra water storage capacity. These measures are intended to allow the expanded canal to operate without the construction of new reservoirs.

Building the new canal

On September 3, 2007, thousands of Panamanians stood across from Paraíso Hill in Panama to witness a huge initial explosion and the launch of the expansion program. The first phase of the project was the dry excavations of the 218 meter (715 ft) wide trench connecting the Culebra Cut with the Pacific coast, removing 47 million cubic meters of earth and rock.

It was announced in July 2009, that the Belgian dredging company ‘Jan De Nul’, together with a consortium of contractors consisting of the Spanish ‘Sacyr Vallehermoso’, the Italian ‘Impregilo’ and the Panamanian company ‘Grupo Cusa’, had been awarded the contract to build the six new locks. The contract awarded to the Belgian company for dredging works amounts to US$100 million over the next few years and means a great load of work for the company‘s construction division. The design of the locks is a carbon copy of the Berendrecht lock in Antwerp which the company has helped to build back in 1989. With 68m width and 500m length, this is the largest lock in the world to date.

For mutual benefits in globalizing world

Panama’s new locks are expected to open for traffic in 2015. The present locks, which will be 100 years old by that time, will then be able to give engineers greater access for maintenance, and are projected to continue operating indefinitely.

The project is designed to allow for an anticipated growth in traffic from 280 million PC/UMS tons in 2005 to nearly 510 million PC/UMS tons in 2025. The expanded canal will have a maximum sustainable capacity of approximately 600 million PC/UMS tons per year. Tolls will continue to be calculated based on vessel tonnage, and will not depend on the locks used.

“The project will benefit the people of Panama, the shipping/maritime industry and world trade. Panama’s geographic location is its destiny – we aim to be at the center of global trade and become a great maritime hub,” said Alberto Alemán Zubieta, ACP administrator/CEO. “Expansion will be a principles-driven project – we are committed to transparency, efficiency and environmental sustainability. This will guide our vision and direction.” We can look forward to the strengthening of one of the world’s critical trade arteries; allowing the vital ‘All-Water Route’ to continue to grow and create more efficient service at the Canal. Following the objective to tighten the global supply chain and bringing goods to market faster, this venture helps to save time and money for producers and consumers all over the globe.